by biomed | Jul 14, 2020 | News

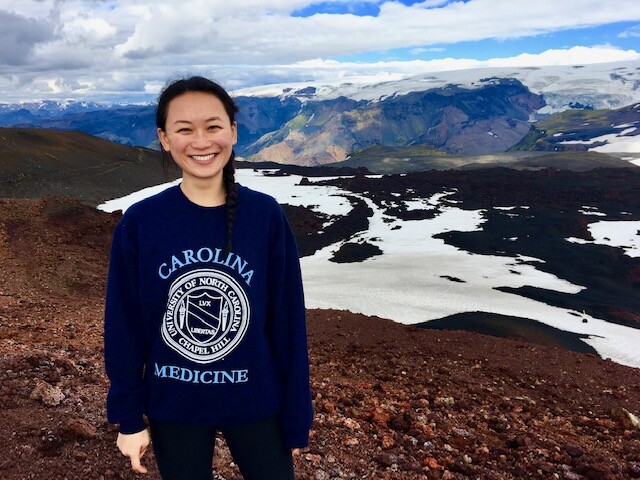

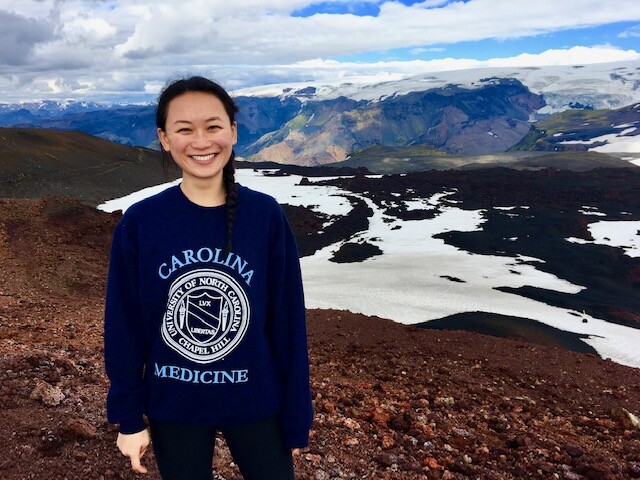

Agriculture farmers will tell you that a successful season is built upon patience, risk taking, hard work and favorable conditions. The similarities to successful research are obvious. Boya Wang is a modern-day farmer in biomedical research where her current work focuses on the development of tests to better diagnose solid and liquid cancers. When cancer cells die, they release free floating DNA into the blood. Boya is working to develop tests to sequence DNA from patient’s blood samples. This would allow her to detect DNA released by cancer cells. “Many times, the cancer DNA is very low and so you come across the problem of trying to find a needle in a haystack – where the needle is the cancer DNA.” Boya explained. Her excitement to work in this field stems from the potential she sees in industry and in public-private partnerships. “This field is an example of successful translational research. There are many academic labs and private companies who are developing these blood tests. There have been promising clinical trial results and even more ongoing trials. Ultimately, I hope to contribute as much as possible during my current training and in the future with my goal of being a physician scientist.”

After completing her degree in Chemistry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill(UNC), Boya decided to pursue an MD/PhD. This decision was inspired by her mentors at the at UNC Cystic Fibrosis Center who taught her how research could benefit patients and how patients could influence research. Throughout her undergraduate, Boya led a nonprofit organization to establish a medical lab in Lawra, Ghana. After graduation, she worked in the lab of Dr. Camille Ehre at UNC. Boya used primary human epithelial cell models to investigate new compounds which break down mucus in patients with obstructive lung disease. This work was published in American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. In total, Boya’s research experience motivated her to address questions with clinical relevance and learn bioinformatic skills applicable to a range of topics. She could not imagine a more exciting career and was enthusiastic to become an MD/PhD Scholar through NIH OxCam and UNC. After completing two years of medical school, Boya started her PhD in 2019 collaborating between Dr. Louis Staudt (NIH – National Cancer Institute) and Drs. Nitzan Rosenfeld/Carlos Caldas (University of Cambridge – Cancer Research UK).

Due to COVID-19, Boya left the UK and returned to the NIH. Her mentors and the NIH-OxCam Scholars Program provided significant support and flexibility to adapt to unusual circumstances. Boya’s mentors helped shape her project to include both lab work and data analysis to better adapt to changing circumstances. Outside of the lab, she is a member of the student leadership board (SLB) and works in concert with fellow students to help welcome the incoming NIH-OxCam class.

by biomed | Jul 10, 2020 | News

Congratulations to all of the winners of the 2020 Lasker Essay Contest. This year, the Lasker Foundation’s annual Essay Contest invited scientists to describe how a notable scientist has inspired them – through the scientist’s personality, life experiences, and/or through their scientific contributions. With hundreds of essays submitted from contestants around the world, the Lasker Foundation awarded eleven essays write by Emily Ashkin, David Basta, Avash Das, William Dunn, Safwan Elkhatib, Laurel Gabler, Kwabena Kusi-Mensah, Lisa Learman, Olivia Lucero, Hannah Mason, and Samantha Wong, respectively. To learn about the winners and read their essays, visit the Lasker Foundation.

One name may look familiar, as NIH Oxford-Cambridge Scholar Hannah Mason has been named a winner of the 2020 Lasker Essay Contest. Hannah is a fourth year NIH-Cambridge Scholar pursuing her PhD in the laboratories of Dorian McGavern at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and Ole Paulsen at the University of Cambridge. She studies how the brain’s immune system responds to and is shaped by repetitive head injury and degenerative processes. After Hannah completes her PhD, she will return to her home state of Georgia to attend medical school at Emory University. She hopes one day to be physician-scientist designing therapies and treating people with neurodegenerative diseases. Here is the winning essay from Scholar Hannah Mason:

My Gym Genie: Gathering Inspiration from Dr. John Schiller

I remember the first time I met Dr. John Schiller. I was interviewing for a PhD program at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The morning’s interview hadn’t gone well, and I just knew I wouldn’t get into the program. I had dreamed of training at the NIH, of discovering a druggable target for neurodegenerative diseases, but now I had to go back in and pretend that those dreams weren’t slipping away. Sitting down for the interview lunch, I never expected to be across the table from someone who had effectively cured a disease that plagued my childhood, someone who would one day become a mentor to me. I sat down across from Dr. John Schiller and was immediately thrown back in time.

I was back in elementary school, sitting on Mrs. Gazeley’s waterbed on my tenth birthday playing Sorry and watching The Ellen DeGeneres Show. I knew she did not have much time left. I just did not know how little.

I do not remember when I first learned of HPV. Trying to pinpoint the date is like trying to figure out the first time I read a chapter book. I can ballpark a period of time, but the exact date seems inconsequential because once I learned, it just became part of everyday life – a chapter a day. In my memory, Mrs. Gazeley, my mom’s best friend and a constant in my childhood, had always had cervical cancer. She had had it in college, and it was back. At the time, I did not understand how she got it, but I knew it was not something she wanted to have. It meant days spent getting chemotherapy at the Oregon Health and Science University. It meant losing her hair. It meant dying.

Until it did not. Two years after Mrs. Gazeley’s death, Gardasil became FDA approved as a preventative measure for HPV and therefore cervical cancer. My mom, usually someone to stay away from any medicine that is not tried and true, had my sister and me first in line at our pediatrician’s office for the vaccine. We were not going to experience what her friend had gone through, not if she could help it. I remember the three shots making my arm sore for days, but each time we went, I knew I was preventing a disease that had both broken me and made me committed to helping people suffering from incurable diseases.

So, as I returned to lunch that day, I realized that I was meeting a great. I was meeting John Schiller, the man who had helped discover and develop the vaccine that protected me from a similar fate to Mrs. Gazeley. I was meeting someone that had accomplished the purest goal in biomedical science – bringing a discovery to people and preventing disease.

Despite my earlier fears, a few months later I found myself a graduate student at the NIH. I was constantly seeing legends of science around campus from Tony Fauci to Steven Rosenberg. No scientist, however, inspired me quite like John Schiller. Occasionally, I would see him at the tiny, windowless campus gym. He always had a smile on his face. Perhaps it was the endorphins, but I liked to think it was just his disposition. Dr. Schiller would ask me how the science was going. As

a first year PhD student, the science was going about how trudging through half melted snow goes – difficult and sloppy. Dr. Schiller, though, would always take a minute and offer his thoughts on whatever idea or hypothesis I was toying with that day. He was my gym genie but instead of offering wishes, he was giving me ideas and advice on how to be a good scientist.

Like any PhD, mine has been fraught with obstacles – mentors lost, projects scooped. Many days I find myself thinking is it all worth it? Will my science ever help people, or is it destined to sit in PubMed for eternity, occasionally cited, but mostly forgotten? I did not start an 8-year path to become a physician-scientist for this, I think to myself. Then I remember John Schiller. I remember his gym words of wisdom on selecting problems that really matter, coming up with a solution, and knowing when to hand a discovery off to the next person in the pipeline to develop. I remember that the goal is always to help patients, not our own egos. I remember John Schiller, who is to me, everything that a scientist should be. He recognizes that science is a team sport. He is focused on improving human health. He is a mentor. I remember John Schiller, and I remember that I, too, can achieve my dreams of making a difference in people’s lives through science.

by biomed | Jun 13, 2020 | News

Dr. Matt Maciejewski, an Associate Director at Pfizer, Alliance Alumni Director, and the first alumnus of the Wellcome Trust – NIH PhD program recently took it upon himself to implement a few of the available methods for correcting the Covid-19 underreporting, and created a simple web-app that can be freely used to visualize the true case number estimates. An accompanying writeup is available on Medium. For those interested in the code behind the app, Matt made it available on GitHub.

by biomed | Jun 12, 2020 | News

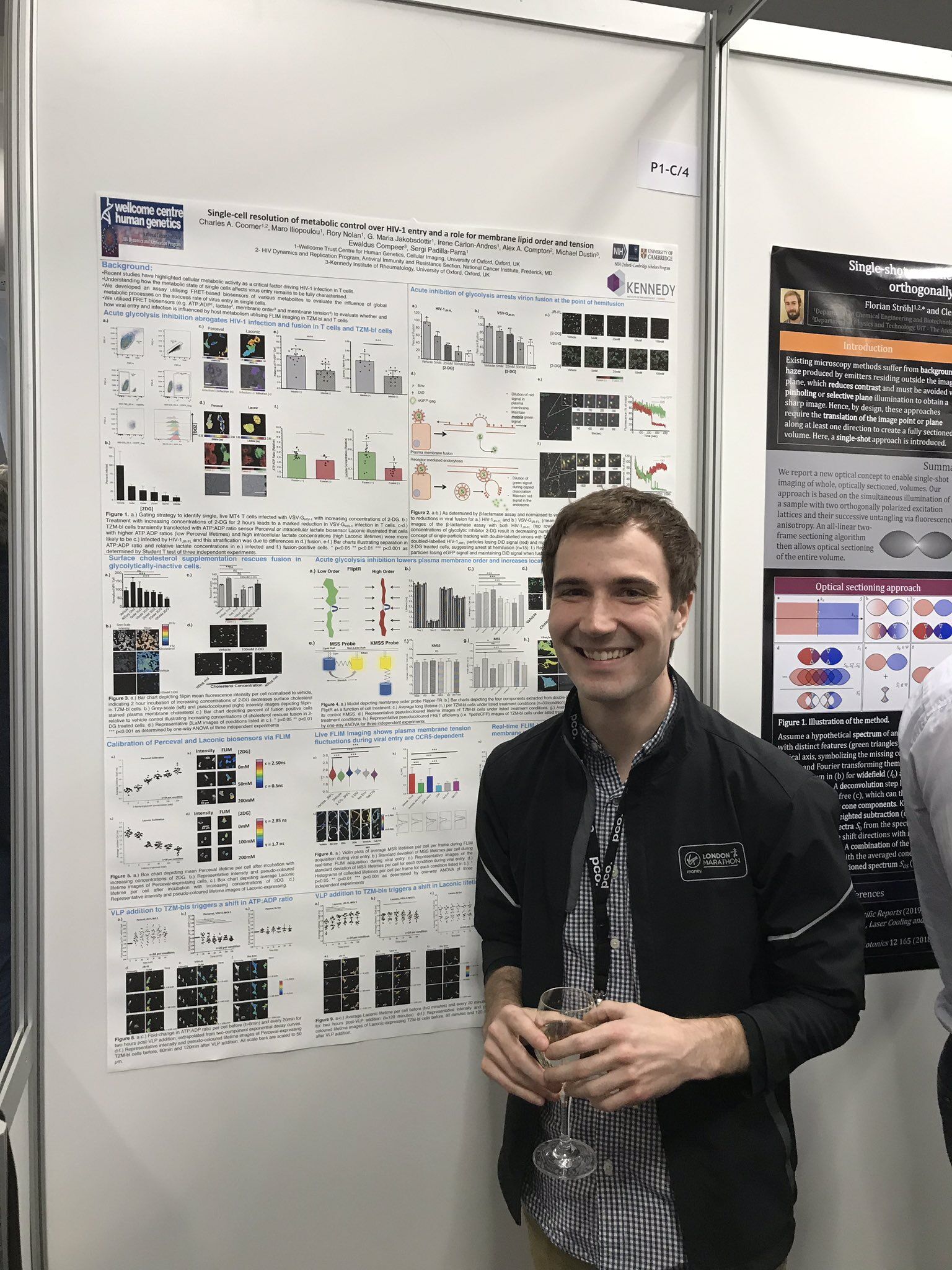

The road to obtaining an MD/PhD is not a sprint but a marathon. As Charles (Chad) Coomer well knows. It’s long, grueling, requires incredible endurance, but worth every millisecond.

Chad is completing his MD/PhD degrees at the University of Kentucky (MD) and the University of Oxford (DPhil) under the mentorship of Drs. Alex Compton (NIH/NCI) and Sergi Padilla-Parra (University of Oxford). As an undergraduate student at Western Kentucky University (WKU), Chad worked with Dr. Rodney King to identify and characterize novel bacteriophages to target Mycobacterium species. Through this work, Chad was awarded a Goldwater Scholarship, solidifying his commitment to basic research and to apply the tools learned in his undergraduate laboratory to those at the HIV Dynamics and Replication Program at the NIH/NCI as a summer intern. This work ultimately led to Chad to apply to a Fulbright Scholarship at University College London (UCL) in 2014, where Chad fostered his love of virology and translational medicine by investigating mechanisms of protease inhibitor resistance under Ravi Gupta. Ultimately, his experiences at UCL and in the UK during his Fulbright year motivated him to apply for the NIH Oxford-Cambridge Scholars program.

His work has highlighted the role of several biophysical properties of cell membranes in the context of virus entry, particularly that of HIV-1. To accomplish this, he has developed several advanced microscopy tools in the Padilla-Parra lab, particularly by multiplexing single-virus tracking and fluorescent lifetime imaging microscopy. These tools identified key metabolic influences of host cell membrane properties that facilitate HIV-1 fusion in target cells, which is now published in PLoS Pathogens (https://journals.plos.org/plospathogens/article/comments?id=10.1371/journal.ppat.1008359). By utilizing these tools he developed at Oxford, Chad’s research is currently devoted to understanding how a protein called IFITM3 functions to prevent virus entry. The results of these studies are currently under review, but can be read on bioRxiv (https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.05.14.096891v1).

Chad will be defending his thesis in April 2021. Following successful completion of his PhD, Chad will return to the medical school to finish his clinical training at the University of Kentucky College of Medicine. Upon his completion of his MD/PhD degrees, Chad hopes to complete his residency in internal medicine and pediatrics whist continuing to investigate the mechanism of cell-intrinsic antiviral proteins in preventing virus infection. His goal is to become an investigator and lecturer at an academic clinical center to train the next generation of clinical scientists.

In his free time, Chad runs competitively for the University of Oxford and the Montgomery County Road Runners. Currently, he is also serving on the NIH COVID19 task force by assisting the testing site at the NIH. Chad often compares completing MD/PhD training to that of running a marathon. “You have to respect the distance,” Chad says, “as each person who’s running this race will train differently to you and complete it (their training) at a different pace. Training for marathon, or as an MD/PhD does not have a ‘one size fits all’ approach, but there are definitely correlates of success: consistency, recovery, and having amazing teammates. The NIH OxCam program is a perfect regimen that definitely incorporates these three factors at the core of their training.”

by biomed | Jun 12, 2020 | News

Jessica van Loben Sels is completing her DPhil in Pathology under the mentorship of Dr. Kim Green at the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Disease and Pr. Ian Goodfellow at the University of Cambridge. Her work has led to the development of several serological assays to monitor duration and breadth of protectivity in patient serum antibodies against human norovirus. She deployed one assay in the field with the help of collaborator Pr. Stephen Baker at the University of Oxford Tropical Disease Center in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, where she screened infants for protective immunity against a variety of norovirus strains. Her project has elucidated immunological patterns which can inform multivalent vaccine design. Her work as also led to the identification of potentially broadly protective immunoglobulins which can help map important epitopes on the virus and serve as treatment for immunocompromised individuals who are suffering from chronic norovirus infections if the antibodies show therapeutic potential.

She is set to submit her thesis in August 2020. Immediately following submission, she will begin working towards her Masters in Public Health at the George Washington University in Washington, D.C. Her work throughout graduate school has been focused on understanding immunity and disease transmission within vulnerable populations in low- to middle-income countries (i.e. children in Vietnam). Having gained months of international field experience working with various peoples and governments to accomplish scientific goals, she decided she wanted to make a career out of field epidemiology. Upon the COVID-19 outbreak, she has worked with the NIH on the contact tracing team and gained valuable insight into the many facets of public health that respond to disease outbreaks. It is for this reason she decided to pick the concentration of Global Health Epidemiology and Disease Control for her MPH studies. Following the completion of the two-year program, she aspires to be trained by the CDC in the Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) fellowship program and attain a career in aiding state and federal governments respond to public health crises.