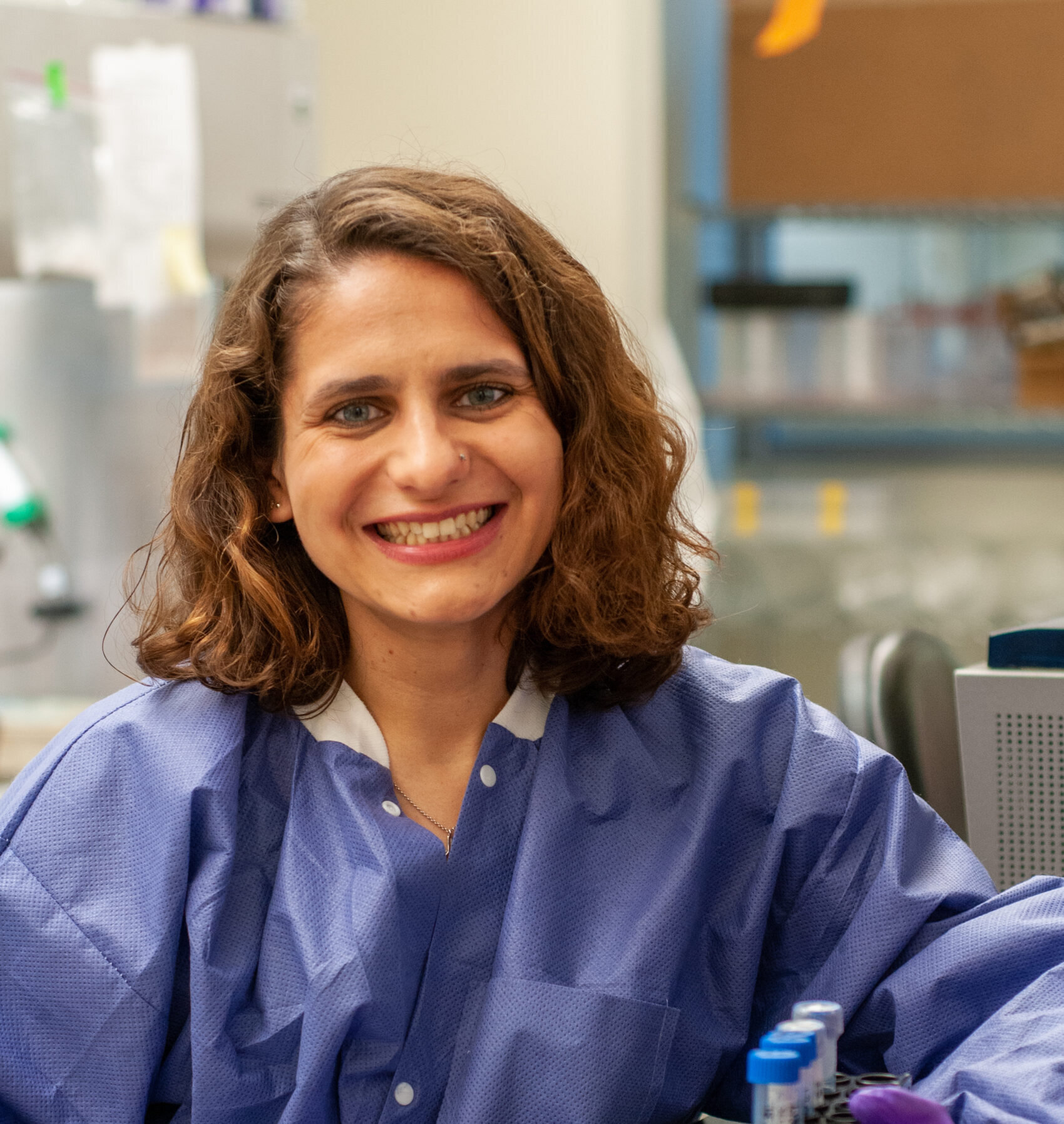

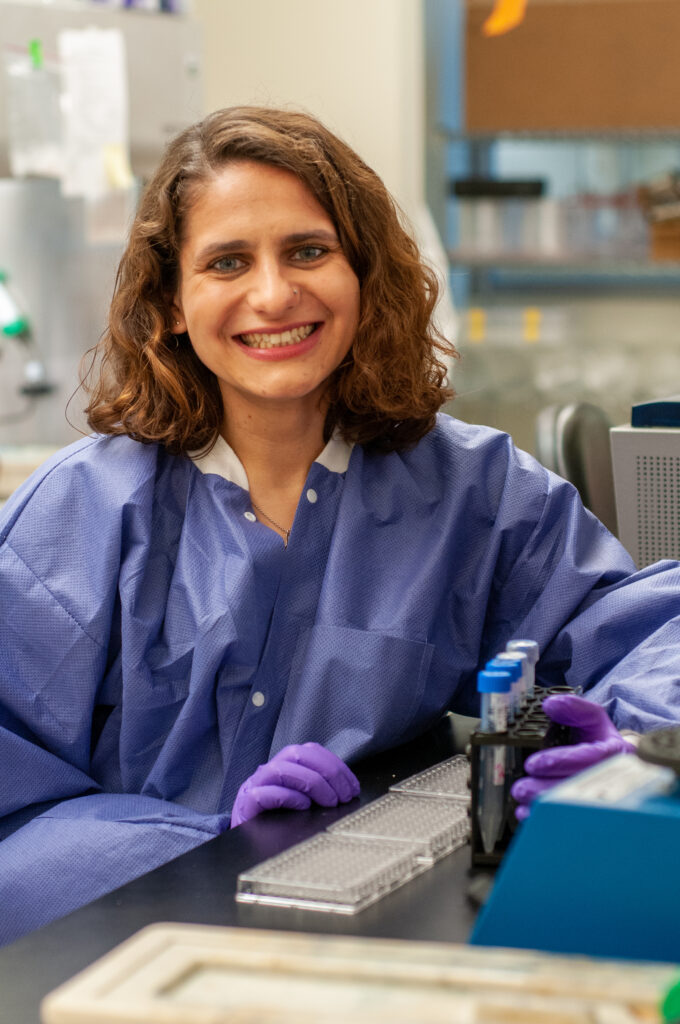

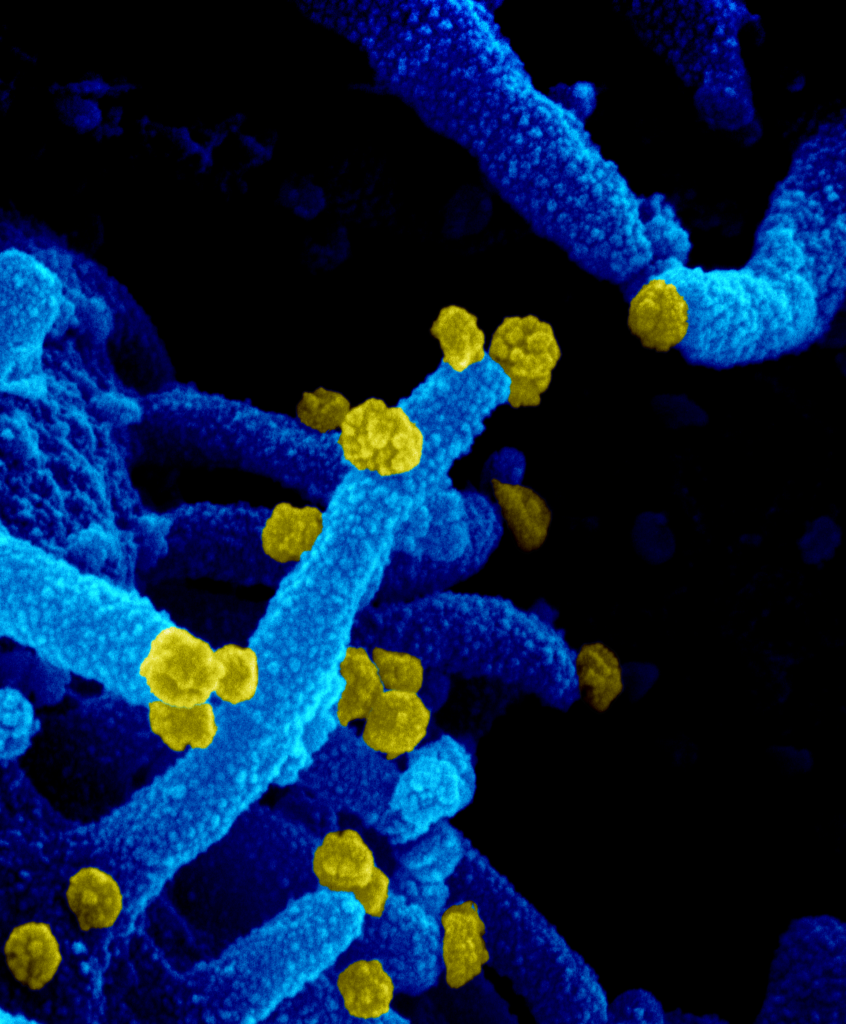

A Science Fair Enthusiast Emerges as a Future Physician-Scientist During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Did you notice the Alliance’s new homepage image? Are you curious about what this image depicts? Vicky graciously let us use her scanning electron microscope image showing SARS-CoV-2—also known as 2019-nCoV, the virus that causes COVID-19—isolated from a patient in the U.S. (which is highlighted in the text below), emerging from the surface of cells cultured in her lab. We were excited to feature a new image that highlights one of our Scholars’ work, while also being extremely relevant to the times! For this Scholar update, we check in with NIH-Oxford MD/DPhil Scholar Victoria (Vicky) Avanzato to hear her story.

With students heading back to school across the country, science teachers have developed their curriculums to include lessons and experiments. Throughout the year, students will have the opportunity to create their own experiments and participate in science fairs. Science fairs challenge students to identify a question, develop a hypothesis to answer it, and then devise an experiment to test that idea. In principle, students who participate will not only learn about science but may be inspired to join the next generation of future leaders in biomedical research and medicine. This rang true for Vicky, who became interested in science at a young age through participating in science fair projects with her father. Vicky’s interest in science, specifically infectious diseases, developed during her studies at Pennsylvania State University. She doubled majored in Immunology and Infectious Disease, and Toxicology and participated in two summer internships, one at the Mayo Clinic working on oncolytic virotherapy against endometrial cancer, and another at the University of Texas Medical Branch, where she helped study the immune response to dengue virus. Through these internships, Vicky discovered her passion for virology and global health and decided to pursue her MD through Emory University School of Medicine, and her Ph.D. through the NIH Oxford-Cambridge Scholars Program. Vicky joined the laboratories of Dr. Vincent Munster at the NIH Rocky Mountain Laboratories and Prof. Thomas A. Bowden in the Division of Structural Biology at the University of Oxford, studying the immune response to the Nipah virus, a bat-borne virus infection. For this work, Vicky was awarded the Norman P. Salzman Memorial Graduate Student Award in Basic and Clinical Virology, as well as the Fellows Award for Research Excellence and NIH Women Scientists Advisors (WSA) Scholar Award.

At the University of Oxford, Vicky’s work focused on studying antibodies against the Nipah virus, a re-emerging virus that causes severe disease in humans. Using structural biology techniques, Vicky was able to determine where the antibodies bind the proteins on the virus, which allows the identification of vulnerable sites on the virus surface that can be targeted by the immune system. At the NIH, Vicky was also able to show that these antibodies were able to protect hamsters from getting sick with the Nipah virus, suggesting that the sites on the virus targeted by these antibodies make an attractive target for the development of vaccines and therapeutics. Her work on one of the antibodies, termed mAb66, is published in PNAS.

When the COVID-19 pandemic began, Vicky’s Oxford and NIH labs shifted to focus on the pandemic response. Vicky was able to produce SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and optimize the serology assays in the lab, which were critical to study the antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination for animal studies and patients sample analysis. She also studied long-term SARS-CoV-2 shedding from an immunocompromised patient with cancer. The study, published in Cell, shows that the patient had a persistent COVID-19 infection and shed infectious virus for 70 days, and also displayed significant viral evolution over the course of the infection.

“The sudden shift in work was initially difficult for me – it was a big change from the initial Nipah work I was invested in and also a stressful time in general with a pandemic. However, I was able to apply my protein skills from my Oxford lab to my SARS-CoV-2 antibody studies at the NIH and I also learned many new skills in basic virology in a short amount of time. I hope to bring this ability to be flexible and adapt my skills to new research projects forward in my career as a physician-scientist,” remarked Vicky.

As her time in the program draws to a close, Vicky said she is grateful that she got to experience such diverse opportunities, both scientifically and personally, during her training. “I had such a broad training experience and learned a lot of scientific skills between my two labs. I was able to work on antibody structures, as well as participate in the pandemic response, which was really a unique way to spend graduate school. Outside of the lab, I also pursued my interests in music and hiking. At Oxford, I played the French horn and was the president of the Oxford Millennium Orchestra. I was able to play quite a few symphonies, including Mahler 1, and it was really a dream! My time at RML in Montana was like another world – I loved exploring the wilderness and hiking mountains on the weekends and taking little trips to Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks. My time in the Program really brought together the best of these very different places.”

After completing her Ph.D., Vicky plans to return to finish her medical degree at Emory University School of Medicine. She then hopes to complete a residency to become an infectious disease physician, while continuing to pursue her research interests in antibody responses to emerging viral infections and global health.